Twenty Lessons from the College Application Process

Coping with uncertainty and cautionary tales

Watching my son apply to college (for the Class of ’29) has probably been the greatest period of crushing uncertainty in my life. Getting into the right school can have profound effects on the rest of your life, especially if you are pursuing particular careers (e.g., finance, law school, medical school). This essay is about many of the lessons I, as a parent, learned through this process, many having to do with efforts people make to reduce the uncertainty and how these often do not achieve their intended ends. This essay is not for everyone. It is primarily for parents who thinks their child might have a chance at getting into a top 25 school and want to do the work and planning to get there. If you are certain your child is going to a top 25 school, this might not be for you. If your child is aiming for a top 50 school, there is probably some useful stuff in here, but I think your child might be subject to a fundamentally different admissions process (see Lesson 2). Wherever you and your child are aiming for, there is no judgment. I myself did not go to a top 50 school and I had a great experience that set me up for life very well. I am simply pointing out that this essay will have more relevant information for families aiming for a top 25 school.

If you just want the highlights, I recommend jumping to Lesson 3 (Decide on your child’s narrative early), Lesson 6 (The statistics are nearly meaningless), Lesson 8 (Fit often trumps statistics), Lesson 12 (Early decision is mostly a yield protection scam), Lesson 13 (Regular decision is better?), and Lesson 19 (The cautionary tale is not what you think).

Let me describe the two visions I held throughout the process and if this feels familiar, then this is the essay for you. I felt like I had an angel and demon on either shoulder. On the one hand, I had the vision of my son getting into a HYPS (Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford) and while his getting in is a total surprise in this vision, I know his record wouldn’t make people think ‘How the heck did he get in?’ He wouldn’t stick out like a sore thumb. On the other hand, I also had the vision of my son becoming a cautionary tale where we had overestimated the strength of my son’s record and applied to too many schools that were out of his league and my son ends up at a safety school barely in the top 50. Every year, one or more stories go viral of a student who sounds incredibly impressive (top GPA, nearly perfect SATs) who did something extraordinary (started a company that made millions) and gets rejected from every top school in the country. If you are not an insane narcissist, this should give you pause about the merits of mostly applying to the top schools. Near the very end of this essay, I give two real examples of these cautionary tales (Lesson 19) and discuss why they might not be what they seem. That said, these two visions of my son as the admissions overachiever and as the next cautionary tale have fought each other in my brain for the last two years.

The fundamental issue is that you don’t know how your child’s application will be seen by each university. By the end of the process, you might have a clear picture (we did), but going forwards, there is almost nothing but crushing uncertainty. As I will discuss, parents do all sorts of things in order to try to reduce this uncertainty, but a lot of these fail to achieve their ends and in some cases, it feels like others are preying on our fears and uncertainty for their own benefit.

A note about terminology. I will refer to top 10, top 25, and top 50 schools as a shorthand. This is roughly based on the U.S. News & World Report college rankings. These are far from perfect rankings, but they are widely referred to and so useful. Also, if I say top 50, I typically mean schools ranked closer to this number, like schools ranked 40th to 50th. If I say top 20, I probably mean schools ranked 16th to 20th because if I want to refer to a higher ranked school, I will use a different number. Finally, while I think going to an elite college (e.g. HYPS, top 10) can have a big impact on a child’s future, what the student does wherever they are in school will usually have a bigger impact. Let’s not forget that CEOs of top companies have often come from mid-tier schools or schools you have never heard of (e.g., Steve Jobs, Jamie Dimon, Satya Nadella)

Lesson 1 – Who decides your fate at each college? Although there is a committee of admissions officers at each school who will vote on your child’s application, it mostly comes down to one admissions officer (AO) who will read all of the applications from your geographical region. That one person then becomes your advocate (or opposition) as they present your child’s case to the rest of the committee. If the one reader gives you a thumbs up, you have a decent chance of getting in and if they give you the thumbs down, you almost certainly will not get in.

Here are two things to know about this person. They probably majored in the humanities or social sciences. Many fewer STEM and business majors go on to become admissions officers. The second thing to remember is that each person sees the world through their particular lenses including this AO. You are going to get a potentially very different read from your one AO at different universities. Every year there are a handful of students that are so compelling that they get into almost all of the top schools. But many students who get into a top 10 school are rejected from all of the other top 10 schools. This has to do with your child’s fit (more on this below) and the particular way your AO at each school reads your child’s application.

Lesson 2 – Be one-of-one. At top 50 schools, particularly those with larger student populations, the admissions process appears to be a bit more impersonal. GPA, SAT, AP scores, list of ECs, plus no red flags may be enough to get you in. When you are reading 90,000 applications for 10,000 spots, I suspect outcomes are a bit more algorithmic.

For top 10 schools, I think it is more like casting actors for a film based on their demo reels. The AO really has to fall in love, at least a little, with each student they are going to admit. For this to happen, your student needs to look singular on paper – be one of one. Of course, there are bad ways to look singular like ‘I hope to become a con artist one day and make money at the expense of struggling families’. You can also look singular by looking like a mess where you have dabbled in everything but there is no obvious core driving the plotline of your efforts so far. I bet this isn’t so singular, but it definitely isn’t good for admissions.

Instead, you want them to see an authentic compelling narrative of who your child has been and where they are headed that makes the admissions officer think ‘I found one! I’ve seen application after application, and I finally found the student we need to have at Princeton. They will make our community stronger and go on to do great things that benefit society after they graduate.’ The best-known version of these are something along the lines of ‘I overcame terrible odds and serious hardship, but still excelled and found ways to give back to my community.’ That’s a great story, but it is not the only story. None of my son’s friends have heroic hardship stories and they were very successful. Also, don’t undersell your child. You might be thinking ‘how could my son who doesn’t clean his room and loves to play Magic the Gathering all the time be the kid they see that way?’ But this isn’t how the AO sees your child and it’s all in how your child frames the things they have spent time on.

Lesson 3 – Decide on your child’s narrative early. I give a lecture each year to UCLA undergraduates on how to apply to graduate school and I teach them about creating a narrative to convey how the things they have done in college point to who they will be in graduate school. Admissions involves looking at a handful of documents, trying to see a three-dimensional person, and then deciding, on that basis, whether to invite someone to be in our community for years. If your child has done a bunch of random extracurriculars (ECs) and summer workshops on unrelated topics, the schools they apply to won’t know who they are – they won’t come together for the AO as a coherent individual. Just like you, the schools are also trying to reduce uncertainty.

If your child is in 8th, 9th, or maybe even 10th grade, I recommend that you figure out what your child’s narrative might be when they apply to college. This story needs to be an authentic reflection of who your child is, as best that you can tell, and then that story should guide everything your child does until they apply to college. It is much easier to create a narrative and follow that with actions that support that narrative then to do whatever seems interesting along the way and then have to try to craft a narrative from all of that, whatever that happens to be, in retrospect. To be clear, I suspect lots of people get into top schools without doing this, but I think if you can do this, it will increase your odds because it will increase the alignment between what your child says about themselves and what they can point to as evidence from what they have been doing.

For us, when my son finished 8th grade and clearly had ambitions to go to a top college, I had a conversation with him and said that he needed a plan for what story he wanted to tell about himself four years later when he applied to college. I told him that once he got to college it was 100% up to him whether he wanted to stick with or abandon the plan. But this plan was going to guide his classwork, ECs, and summer activities so that four years later he would be able to say “I have a clear vision of what I want to do and all my past activities back up this story.” For my son, that clear vision was wanting to be ‘an entrepreneur who develops education and mental health ventures’. He had imagined running companies since he was five years old and so it seemed like a good fit (and luckily, still is, four years later). In particular, my son was interested in someday getting into VR-based immersive educational experiences. So, my son’s narrative plan was clear: businesss/entrepreneurship, education, and psychology/mental health.

Obviously, your child’s narrative need not and probably should not look like my son’s. But it has to be authentic for your child. Fabricated narratives almost always give themselves away and will surely lead your child to be rejected. Also, your child’s narrative should say something about how they are going to improve the world and make life better for some group of people. There are a million ways to do the latter – being a heart surgeon ticks this box for sure, but so does wanting to do comedy to bring moments of joy to people’s lives. The key thing is to focus, at least in part, on how your child plans to leave the world a better place than they found it.

Lesson 4 – Lean into the narrative. Once you have decided on a narrative, get to work backing that up with the classes, ECs, and summer activities your child does. I want to say early on in this process that we are in a very fortunate position. My wife and I are both reasonably well-paid and we only have one child, so we don’t have to split our resources and time with multiple kids. What we did with my son won’t work for everyone. But if there is one thing I am confident of, it’s that college admissions officers are really good at taking into account your environment and the opportunities you have. If you have to work 20 hours/week (like I did as a kid), they will understand why you didn’t have time to do endless ECs.

For my son, everything he did centered around learning about business, developing skills that would help him in business, and trying to build ventures related to education and mental health. For instance, his electives were courses in economics, entrepreneurship, and four years of computer science. He developed a program that helped middle schoolers learn how to study more effectively based on psychology research on learning and memory. To start this program, he met with UCLA cognitive psychologists to get up to speed on the latest research. He contacted hundreds of administrators at high schools around the country. Ultimately, he got several schools across seven states to let him teach their middle schoolers and it was very successful. (Pro-tip: if you do something like this, have your child get testimonials from the people they help. Those quotes will be helpful when you apply). He started another venture that would give high school students training in the statistical coding language R and in Qualtrics, an online survey tool, that would make it easier for them to then approach professors to get real research experience at a local university. He also tried to develop online tools for men’s mental health and for letting high school students connect with peer counselors anonymously online. These and other ventures he started, all showed that he was motivated to be ‘an entrepreneur who develops education and mental health ventures’ and was backing this up with his actions. My son also did multiple summer programs in entrepreneurship and business that we paid for. These were absolutely a mixed bag, and not everyone can do these programs, but they helped reinforce the message that my son knew who he was and what he was trying to become. My son did none of the traditional ECs (student government, yearbook, etc.) which felt risky, but these were unrelated to his plan, so he skipped them. He did play varsity tennis for a few years.

Of course, my son had to have the energy and ambition to follow through on his plan. Part of what makes my son special is that he totally did. But the plan was essential in making sure that everything he did helped tell a singular story about who he was and what he saw as his future contributions to society. Again, there are other ways to help your child stand out, but I think this is a pretty good one.

Lesson 5 – Apply broadly but play the slots. Just like managing a financial portfolio, when your child applies to college you want to apply to a combination of schools that are high risk/high reward and others that are low risk/low reward. This combination simultaneously addresses your fears of underestimating and overestimating how the schools will view your child. But you have to figure out how to balance applications to these two types of schools and your child will only have so much bandwidth to write and submit applications, so you cannot apply everywhere.

My son applied to 30 schools. I think this is really the high end of what is feasible. He did this because we all had lots of uncertainty and also, because my son is a grinder who can work and work and work. That said, 30 was too many and it got really chaotic at the end.

Let me tell you what my son did do and what we would do next time if we had to do it over, knowing what we know now. My son applied to about 1/3rd schools that were dream schools, 1/3rd schools that were sensible reaches and targets that he would have been excited to go to, and 1/3rd schools that were safeties that he wasn’t that excited about. What should he have done? Fewer safeties and more dream schools. Of his 10 safeties he got into six and waitlisted at three others. These were all quality schools, but he felt equally lukewarm about all of them. These were protection against becoming the worst version of a cautionary tale. He only needed only a handful of these to address that concern.

Remember I said in lesson 2 that mid-tier and larger schools probably choose their students more algorithmically – using a bit more of a formula? That means your results at these schools are likely to be more predictable. If you have good advising, they will have a good handle on what your child’s safeties should be and your child will get into some of those. For most that my son didn’t get into, he got waitlisted and I’m confident he would have ultimately gotten into one or more of those. I’ll say more about this in lesson 14. In the end, I think five safeties would have been more than enough to nearly guarantee he would have gotten into two.

While the mid-tier schools may be algorithmic, for the top 10 schools you are looking for a single AO to fall in love with your child’s narrative and each AO will see the narrative differently. So here it is much more like playing Vegas slots, which means that the more pulls of the one-armed bandit you can get, the better your odds of one of them hitting the jackpot. Remember, you shouldn’t really care about the probability of getting into any particular top school. Rather, you want to know the probability of getting into at least one. No one ever provides this information. If I was starting a college counseling company, this would be one of the first things I would do. The key thing is that this likelihood grows with the number of schools you apply to, as long as application quality doesn’t go down.

Lesson 6 – The statistics are nearly meaningless. One of the ways everyone tries to reduce uncertainty is by looking at the available admissions statistics. I spent hours and hours looking at different ways to estimate my son’s likelihood of getting into different schools. There are at least three kinds of statistics you may have access to when trying to figure this out. First, there are the publicly available statistics like ‘Brown has an 5.7% acceptance rate’ that you can get from a Google search. You can also usually find out how that rate is different for folks who apply early decision (18%) versus regular decision (4%). These numbers don’t really tell you much about your child’s chance of getting in and they don’t even tell you about a random person’s likelihood of getting in. Who has an 5.7% chance of getting in? Almost no one. The person with a 1560 SAT has a higher than 5.7% chance of getting in. The average person actually has a lower than 5.7% chance of getting in.

The key problem with the publicly available statistics is that they aggregate students who are in completely different buckets and you really want to know the statistics for people in your child’s bucket. Consider two buckets with radically different odds of getting in. First, recruited athletes have nearly a 100% acceptance rate and they contribute to a school’s overall acceptance rate. Next, consider a school like NYU, where there might be 50,000 applications from students who have no business applying there and have close to a 0% acceptance rate – those students also contribute to a school’s overall acceptance rate. Between those two extremes, there are probably several more buckets, each with their own acceptance rate. Unless you know this information (which is not publicly available), this kind of statistic might feel like it’s reducing your uncertainty, but it is probably just misdirecting you.

There are a number of apps that can now level up the statistics and do a bit better. These apps take into account a student’s own GPA and SAT scores and tries to give them a percentage likelihood that someone with scores like those will get into a particular school. These break down into two varieties. There are publicly available apps like CollegeVine that estimate the likelihood that anyone with a particular set of scores will get into a particular university. Then there are apps that high schools subscribe to like College Kickstart and Naviance. These have a big advantage in that they feed several years of data from your child’s own high school into the app. Because of this, the app knows how students with scores like your child’s from their high school have fared at different universities. Using this, they can do a more targeted estimate of your child’s likelihood of getting into particular universities, using their scores at their high school’s past performance.

At my son’s high school, they went one step further. They broke the senior class down into GPA ranges and then could show my son for any given university exactly how many students from his high school had applied in the past 5 years and exactly what the outcome was for each student category. He could see if they applied early action or regular decision and whether they got in.

All of these tools are meant to reduce your uncertainty and tell you your odds of getting into particular places. But they are really a mixed bag, mostly because none of them can do the same holistic review that the university is going to do. They are all driven almost exclusively by GPA and SATs which only accounts for about half of the variance in who does and doesn’t get in. These tell you about a student’s academic readiness to perform well with challenging material at top schools. They don’t tell you almost anything about how the school is going to evaluate your child’s narrative; whether the school is going to see them as one-of-one, someone they need to have as a part of their community. I strongly suspect that at top schools it is less about individual scores a student gets for their ECs, rec letters, and essays than how well these elements fit together to tell a coherent story. As the kids say these days, it’s a vibe. What feeling does the AO get when they put all of your child’s materials together. What is the overall picture they see of your child and their potential contributions to that university. Your child could have great ECs and also have great essays, but if these elements are telling different stories, the picture the AO sees will be unclear and your child won’t get in. The way to think about this, roughly, is that you need a certain set of scores to be taken seriously, but after that, it is almost entirely about the overall sense they get of who the applicant is and who they will be.

It is because of this that no statistical model, no matter how fine grained is ever really going to tell you your odds of getting into any top college. No model can tell you whether the particular AO at Columbia University assigned to read your child’s application is going to fall in love in a way that makes them go to bat for your child and get them admitted. None of the statistics capture this.

You want the statistics to guide you and reduce your uncertainty. I use statistics in my daily work and I really wanted to rely on these. My sense is that the statistics can guide you for mid-tier schools because they use quantitative models similar to the apps your child’s high school might subscribe to in order to simplify the workload. They are often admitting 10,000 or more students (in contrast to top schools that often admit a tiny fraction of that), which means they are going to focus more on number crunching than applicants’ idiosyncratic details.

But the top schools simply do not do this. They are gated communities and they really need to fall for someone before they admit them. Side note: The UCs don’t seem to particularly operate like either way I am describing and the outcomes from the UCs make less sense than almost anywhere else. The UCs have a bizarre combination of being highly ranked, admitting very large classes, and refusing to look at test scores even though they are the single best predictor of college performance of anything in the application.

Lesson 7 – Passion projects (uggh!) matter. Let me start by saying I despise the term passion project. It makes my skin crawl a bit. That said, if you want to be seen as one-of-one, this is usually the way to do it. Critically, you need to make sure your child’s narrative, ECs, and passion project all line up in a coherent way. That’s what will really make it work for them. And personally, I don’t think raising money for charity is going to do a lot of work for showing your child’s unique character. An internship doesn’t count either. Basically, if a 1000 people applying are putting down the same thing as you, it will not differentiate you. It might check a box for you and some box-checking is valuable, but it will not make you stand out as one-of-one.

For my son, he did multiple passion projects (still uggh) like the one I already mentioned where he taught middle schoolers around the country how to study and learn better. This was directly on brand for him because it was (a) entrepreneurial and (b) focused on education. It also showcased a lot of hard work that he did on his own to make this happen, but then how he also built a community around it, making it into a service organization that many other students participated in in different roles, like outreach, marketing, and becoming trained as tutors. A project like this helps an AO see the story of your child and how they are making a difference.

My son was tempted to try to start companies to show he could make a lot of money in a venture. My view was that the kinds of folks who become AOs (humanities and social sciences majors) want to see impact that benefits a community more than they want to see how much money you can raise selling widgets. Someone someday might want to hire your child because of how many widgets they can sell, but with AOs it is better to focus on how your aspirations will improve the lives of others (which, I might add, is also not a bad way to live life in general).

Lesson 8 – Fit often trumps statistics. I have mentioned that my son was interested in entrepreneurship and business. So, for many schools he had to decide whether to apply to the college of arts and sciences or to the undergraduate business school. At most schools, if a person applies to the business school and doesn’t get in, they are also rejected from the university overall. It’s all or nothing. Same applies to many engineering programs.

All of the statistics we could find said that applying to undergraduate business schools was a bad idea for my son. It is pretty much a universal rule that it is much more competitive to get into the undergraduate business school than to get into the college of arts and sciences at the same university. For instance, University of Pennsylvania has about a 6.5% acceptance rate, but their business school, Wharton, has an acceptance rate that is half this rate.

My uncertainty alarm was on overdrive in this situation. These schools already have terrible acceptance rates and then applying to business schools was going to make acceptance even less likely? The vision of becoming the cautionary tale was making me think that at some or most of the schools, my son should just apply to the college of arts and sciences and give himself a better chance of getting in. My son ignored the statistics and applied to business schools everywhere he could. He wanted to be a business major and given that conversation we had when he was in 8th grade and all the ECs he had pursued in high school, this is where he fit. He didn’t want to be in arts and sciences if there was a business school there.

In retrospect, we are so lucky my son ignored the statistics. In the end, he got admitted to or was waitlisted at over 80% of the schools with business schools (and most of those were acceptances, not waitlists). You might think, ‘Well, he must just be really impressive. I bet he got in everywhere.’ Personally, I do think he is pretty impressive, but other universities felt differently. At the remaining schools he applied to, schools without an undergraduate business school, he only got into 14% of the schools. Remember, the statistics said he was much more likely to get in applying to arts and sciences, not the more competitive business schools. For our son, these statistics did not apply at all.

My son had a strong GPA and great SATs, but the single clearest factor that determined how his application was perceived was whether that one AO who was reading his application and determining my son’s fate could see my son at their business school. Liberal arts colleges mostly said ‘we don’t see it,’ whereas the AOs slotting people into business schools said ‘he looks like one of us’. Your child should lean into a singular vision of who they might be, organize their classwork and ECs around this, and then when they apply, believe in this vision and apply to the programs where they truly fit even if they have a low statistical likelihood for people in general. Those statistics don’t really apply to you because they do not take fit into account at all and the university will definitely take this into account. We had no idea how much universities cared about fit when we were applying, but the results my son got back were such a clear signal that this played a huge role.

Lesson 9 – Your child’s classmates are the competition. If 50,000 people apply to a college, the college does not compare all of these students to each other. Instead, they put them in different buckets and choose some from each bucket. For instance, they seem to evaluate the folks who say they want to be economics majors separately from those who want to be art history majors. They look at folks from different states or even regions of states separately. But most importantly, they will compare your child to other kids applying from the same high school. The universities don’t know exactly how to compare your child’s 4.2 GPA to the same GPA from a student at a different high school. They can’t even really compare AP scores because maybe your school has better (or worse) AP training.

But the kid at your child’s high school sitting in the same AP Calculus class as your child has the same teacher so the scores are comparable. All the classwork, resources, and ECs available are going to be roughly the same for everyone at your child’s school. Focusing within high schools also does a decent, though not perfect, job of comparing folks with the same socioeconomic status. My son got a really high SAT score. You know who else did – most people at his high school. My son went to a serious college prep school. Among his friend group of about 10 boys, almost all of them got a 1500 or higher on the SAT. My son’s high SAT score at some level means less than someone else who got a 1450 at a high school where the average score is a 1170.

And this is a good thing for colleges to consider because it levels the playing field a bit and takes into account the opportunities, resources, and culture that each kid has (or has not) benefited from. One way to think about this is that it allows them to see how much your child did with the available resources compared to other kids with the same resources. But make no mistake, your child’s biggest competition are the other students from your high school – and this is extra true if your child goes to an elite prep school.

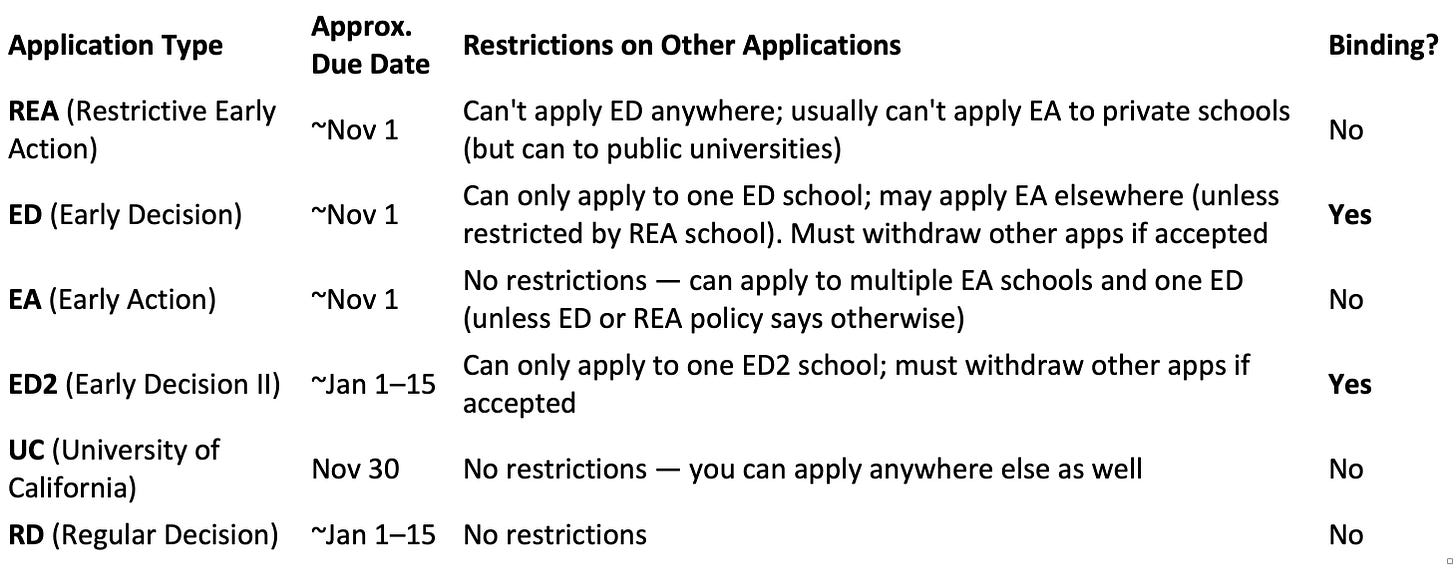

Lesson 10 – ED, EA, REA, ED2, UC, and RD. This lesson is just really practical. There are so many ways to apply to college now that come with different application dates and restrictions on the applicant. Once you understand them, they seem like a valuable route to reduce uncertainty, because your child can ‘place some bets’ that give them a better chance of getting into a couple of top schools. But as we will see in the next lesson, they are mostly a scam where you give up your child’s choices in return for a benefit that often does not exist. The title of this lesson is a list of all the ways that I know of to apply and I’ll briefly describe each so that you have the terminology. I’ve also made a table of all of these below.

Let’s start with early action (EA) and regular decision (RD). Roughly speaking this just refers to the due dates of applications. Most EA applications are due in early November and RD applications are due in early January. Meanwhile all the University of California (UC) applications, covering 10 different schools (including six top 30 schools), are due around November 30th. None of your applications to these particular deadlines influence what other schools you are allowed to apply to. You can submit 10 EA, 10 UC, and 10 RD applications if you want to.

The rules change for early decision (ED), early decision II (ED II), and restrictive early action (REA). These are used by the most prestigious schools and in any given round you can only apply to one of the schools offering these options. The HYPS (Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Stanford) use REA meaning that if you apply to them in the early round, the only other schools you are allowed to apply to in the early round are public universities. If you find out in December that you did not get into your REA school, you are then free to apply anywhere for the RD round. Many other top schools do ED including UPenn, Duke, Brown, Dartmouth, Cornell, Columbia, Northwestern, University of Chicago, Washington University, NYU, and others. You can only apply to one ED school and if you choose this option you cannot apply to an REA school in the early round. The advantage of ED over REA is that you can also apply to private early action schools like MIT and University of Chicago along with your ED school and other public universities. The potential downside to ED is that you have to go there if admitted. ED is a binding agreement and you also are required to withdraw all of your other applications if you get accepted. Of course, get admitted to your ED school might be your ideal outcome, but it becomes your only choice at that point leaving you to wonder what would have happened if you had gotten back decisions from all the schools your child was considering. Finally, a few schools now offer ED II, like University of Chicago, Washington University, Vanderbilt, and NYU which essentially lets students who did not get into their REA/ED school in the early round take another stab at the ED process.

I know that’s a lot, but here’s what that typically looks like in practice. A student will apply to either an REA or ED school along with other EA schools they are allowed to in November, then apply to the UCs at the end of November, then decide whether to do ED II and if so, submit that with all the other RD applications in January. That’s it for this lesson. I just wanted to give you the lay of the land as a set up for the next few lessons.

Lesson 11 – Universities care about acceptance rates and yield rates. Universities care a lot about two metrics: acceptance rates and yield rates. The acceptance rate is the percentage of students who apply and are offered admissions. So, if a school has a 5% acceptance rate, it means that they offer a slot at their university to 1 out of every 20 applicants. The yield rate refers to the percentage of students who, after being offered admission to a school, actually enroll at that school. Schools want a low acceptance rate and a high yield rate. Harvard admits about 3.5% of applicants and of those admitted, 84% choose to enroll at Harvard. So, they have a 3.5% acceptance rate and an 84% yield rate. Those numbers are as good as it gets and a big part of what makes elite schools seem elite to the rest of us. Almost no one gets in and those who do get in almost always say ‘yes’. That’s the definition of an exclusive club.

The acceptance and yield rates can both be gamed in order to artificially make a school appear more prestigious and many universities seem to do this. Back when the pandemic hit, many universities dropped the SAT/ACT requirement. This seemed like a very generous thing to do and maybe it was. But the consequence of this was that many students who had no business applying to schools like Harvard said “If I don’t need to take the SAT, then why not? Let’s give it a shot.” Harvard continued to accept the same number of students as they always had, but their applications jumped from 40,000 the year before covid to 58,000 the next year. As a result, their acceptance rate dropped significantly from a decade earlier. Did Harvard become a better more prestigious school? No. But since more students were applying, it kind of looked like they were.

Lesson 12 – ED is mostly a yield protection scam. If your child has aspirations of going to a top school, then you are probably looking at any way to get a competitive advantage. With over 2 million students applying to college in the U.S. each year and only about 15,000 slots at the top 10 colleges, the odds are pretty depressing. ED seems like a good solution. In essence, you promise a college that they are your one and only – that if they accept you, you will go. You agree to this in advance and have to sign paperwork to this effect. What you give up is the ability to shop around. Remember, you can’t ED to the HYPS. Let’s say your child EDs to Vanderbilt (a fantastic school!) and gets in (hurray!), they no longer have the option to ever apply to the HYPS in the early or regular rounds to see if they could have gotten super lucky. Often times, the ED is a hedge to get into a really great school at the expense of finding out whether your child could have gotten into one of their dream schools. This is exactly what my son did, applying ED to a top 15 school even though his dream schools were two of the HYPS. I kind of felt like we had cracked the code. I figured that in the early round most people aim too high, so if we went down a level from what my son really wanted, maybe he would really stand out and get into an amazing school.

The problem with ED is that it is not at all what it seems. You will see a fair number of top schools with ED acceptance rates around 10-15% when the school’s overall acceptance rate is closer to 5% (which means the RD acceptance rate is even lower). This suggests your child’s probability of getting into a school doubles or even triples when they apply ED. This seems plausible because you are promising to enroll if they accept your child, something that sends a strong signal about how serious your child is about that school and it also helps their yield rate. The increased acceptance rate for ED is real, but it probably won’t help your child.

Remember we talked earlier about how acceptance rates in general aren’t informative because they are lumping together different buckets of students that have different acceptance rates? ED is like that, but on steroids. In fact, the increase in acceptance rates you see in ED at top schools are almost exclusively due to students who are hooked.

I didn’t know the term hooked before we started the process. Hooked is a name given to three types of students who have radically better odds of getting in than everyone else. Legacies, recruited athletes, and the children of highly influential people (major donors, celebrities, politicians). Estimates suggest that at top schools, around 25% of the admitted class are hooked students. Guess when hooked students apply? They pretty much all apply ED or REA. Recruited athletes are essentially pre-accepted and legacies are 4-6 times more likely to get in than other kids.

Once you account for the increased likelihood of hooked kids getting in during the ED round, everyone else has roughly the same probability (or worse!) of getting in as they would in the RD round, but they have given up the potential to get results from any other school. Remember, that apart from the hooked kids, this applicant pool is stacked with students who think their record is good enough to bet it all on that one school. In the end, your child gives up a lot and the school actually gives up nothing when you apply ED. Of the thousands of non-hooked applicants, they choose a few other absolute superstars that they can lock in (and who probably would have gotten accepted in the RD round) and either defer or reject everyone else. ED is a great deal for universities, preying on your fear of your child becoming a cautionary tale, and a lousy deal for your child who gives up potential options.

It’s important to end this lesson with a caveat. Some schools really do use ED in the way that families think they do. From the numbers I’ve seen, if Dartmouth, University of Chicago, or NYU is near the top of your child’s list, those schools really make sense to apply to ED. They really seem to care about the signal you are sending by making them your ED school. The best known example of this is Tulane which accepts 60% of their ED applications, but only 5% of their RD applications. If you promise to only love Tulane, they will probably love you back. If I was looking for a rule of thumb, it might be something like, ‘If the ED acceptance rate is less than 2.5x the overall acceptance rate, then it probably won’t improve your child’s chances of getting in’.

Lesson 13 – RD is better? People apply REA/ED/ED II/EA because the regular round is a bloodbath. And it is. Instead of 5,000-10,000 early applicants to a school, now you might be competing against 50,000-100,000+ applicants. But the applicant pool in the RD round looks very different. First, there are virtually no hooked students applying because they already took slots in the ED round. Second, there are very decent odds that if your child goes to a high-quality high school, some of the most impressive students at that high school got accepted somewhere during the ED or ED II rounds. They are no longer in the applicant pool. Remember, colleges compare your child to other applicants from their high school. If those applicants are out of the applicant pool because they have gotten in somewhere ED, your child isn’t competing against them. Finally, a significant portion of the applicant pool has no shot of getting in. While they are increasing the size of the pool and thus decreasing the overall acceptance rate, they don’t affect your child’s chance of getting in. Finally, the bucket system might be working in your favor. If you have a strong application, but maybe not one of the three strongest applications from your high school, you could end up standing out in the RD round more than if you applied ED/REA and happened to apply to the same school as one of those stars or someone hooked from your high school.

There is no great solution and no guarantees. Getting into top schools is hard (and depends on luck) no matter what, in every round. But when you apply ED, you give up your autonomy for almost nothing in return. Unless you are applying ED to one of your dream schools, it might not be worth it. After getting deferred from his ED school, my son almost applied in the ED II round to another great school. Based on his high school’s track record, my son had good reason to believe he had a strong chance of getting in if he had applied ED II there. But as great of a school as it is, it wasn’t one of my son’s dream schools. On the one hand, we feared this was his last shot to get into a top school. On the other hand, it wasn’t where he was dying to be. So, he made the gutsy decision to roll the dice and just apply everywhere in the RD round and have whatever options he would have. This was really scary for my son because he had mostly gotten into safeties in the early round and received a bunch of deferrals from the higher ranked schools. I really worried that we might come to regret this decision, but I was proud of my son for making it.

Final piece of advice for this lesson. I have been pretty critical of applying ED. But I do think there is a lot of value in applying EA to some safety and target schools. This gets your child acclimated to the process so when your child has a bunch of RD applications to submit in a short time window, they will know how everything works. Additionally, we found that my son’s essay writing got better the more he did. The essays are probably less consequential at the safeties so that is a good place to work out some of the kinks in the stories that your child is going to tell repeatedly, in slightly different formats, in many applications.

Lesson 14 – Yield protection and reverse ED. If your child might be competitive for a top 20 school, you may be surprised when you start to see your child getting rejected or waitlisted at some of your target schools. Our experience was that my son’s safeties typically admitted him, but a level up from there he started getting what, at the time, seemed like surprising rejections and waitlists. There are a couple things to say about this.

First, you are living in a world of uncertainty. At this stage of the process, you are trying to read the tea leaves from every decision you get back. You want to know how each outcome is predictive of the outcomes you will get from the remaining decisions. This is mostly a pointless exercise because each outcome can be spun in your head in multiple ways (see lesson 20 for a personal example). While you may have a pretty clear picture of how schools collectively thought about your child’s applications when you are done, while you are going through it, each outcome is just an anecdote that will loom very large until your child’s next decision comes.

Second, it’s not just the top 10 schools that are trying to game their yield rates through what is called yield protection. Let’s say an applicant is a true superstar. This person will probably apply to at least a few schools ranked in the top 35 (but not much lower). Those schools will look at the applicant and say “Wow, this kid is a superstar. We would love to have them, but there is almost no way they will come to our school. Out of 100 kids with records like this, 95 will not accept our offer and that hurts our yield rate. Since we have no idea which 5 would come, we will reject all 100 of this kind of star application.” Remember that the yield rate is the percentage of students who have been offered admission and actually enroll. Admitting students who are destined to say ‘no’, lowers the yield rate and the apparent prestige of the school.

The waitlist outcome is a particularly sneaky way for lower ranked schools to yield protect. In the scenario I was describing, the school is pretty confident that the superstar will get into a much higher ranked school. When they waitlist a student, it doesn’t affect the yield rate. But then an interesting process places out. Let’s say a top 35 school waitlists your superstar child on March 23rd, expecting your child to get into a top 15 school. The top 35 school will ask your child to indicate whether they want to keep their spot on the waitlist. If your child already has better options by this point, they will usually decline to be put on the waitlist. Even if they keep their spot, if they get into a top school a week later, they will remove themselves from the waitlist at that point. Come May 1st, the waitlist has been whittled down by the applicants mostly to just those who really might still come to the top 35 school. If the superstar is still on the list at that point, perhaps because they were actually the cautionary tale, or perhaps because they have other reasons to prefer the top 35 school (finances, parents went there), then the school will have reason to believe the student really might come and they can offer admission then. In other words, the school can put you on the waitlist not to see if slots open up, but rather to find out if it looks like you will say yes if offered admission. It’s almost like a reverse ED. Instead of you pledging your deep devotion for a school upfront, they are at the bar waiting to see who is still around at 2am.

Yield protection is stupid because the yield rate is a very noisy indicator of prestige. When a California student chooses Stanford over Harvard, is that about prestige or about the parents not wanting their child to go so far away from home? When a California student chooses Berkeley over Stanford, is that because Berkeley is more prestigious or because it is less than half the price (an amazing bargain!). But until someone comes up with a better metric that we all agree is better, schools are going to yield protect by rejecting or waitlisting students they don’t think they can get. What might a better metric look like? I asked the most advanced version of ChatGPT (o3) what metrics would be better indicators of prestige and would be hard to game and I’m pretty impressed with the list it gave me. It’s worth noting that many of these reflect the quality of the students coming in, rather than what the university specifically ads, but being around the best students is, in my opinion, the biggest benefit of being at a top school.

Lesson 15 - Get your saltshaker ready. Everyone has advice and it should all be taken with a grain of salt. My son really wanted to apply REA to one of the HYPS. It was his dream school and he wanted to take his shot. None of us (including him) thought he had a great chance of getting in, but we still believed this was his best shot at getting into a top school. The counter to this was that we did not want my son to be the cautionary tale. Even if REA/ED is your best shot to get into a dream school, you will feel pressure to ED somewhere more sensible. We spoke to three different advisers about whether he should REA to his dream school and got three completely different pieces of advice.

First, we spoke to our high school dean, which at my son’s private high school, is the name they give to the college counselors. We love our dean and are really grateful for his guidance. He looked at my son’s scores and looked at all the students who applied to that particular HYPS from our high school over the past few years and then as gently as he could, said DO NOT apply REA to this HYPS (or any HYPS!).

Next, we went to our college coach, the person we were paying to help my son think about his plan throughout high school and pick which schools to apply to. We really love our coach too because he motivated my son to challenge himself more during high school than he would have otherwise. We asked him and he said my son should DEFINITELY apply REA to this HYPS (or at least to one of the HYPS!). He said that my son had a stronger record than multiple other students he had watched get into the HYPS in recent years.

Both our dean and our coach gave good reasons, but we also thought each might have other motives for what they were saying (which I will get to below). As a result, we wanted to get an unbiased third opinion from someone for whom my son’s outcomes would have no consequences. Someone I know connected me to another college coach he knew. This ‘independent coach’ (to distinguish him from ‘our coach’) agreed to have a call with me to give me his back of the envelope impression. After hearing a bit about my son, he told me in no uncertain terms that not only should my son not apply REA to this HYPS, but that my son should not bother applying at all, even in the regular round, to any of the HYPS. He coaches a lot of students at my son’s high school, which is full of really impressive kids, and told me that my son would be wasting his time because he just couldn’t compete with the other kids applying – many of whom were hooked.

As a psychological scientist, I study how different people see the same events through their own personal lenses and that this leads people to literally see things differently from one another. In this case, I started to wonder about the motivations and perspective of each advisor. Let me say at the outset, that what I say next is how I imagined that each of the three advisors might have come to see things differently. I do not have evidence to back these things up and with the exception of the last one, I don’t think I even believe these anymore. But I think it’s worth considering how different motivations could play a role in the advice you get.

Let’s start with our dean. I think he definitely had my son’s interests at heart, but I could imagine other motives creeping in as well. He is responsible for a bunch of seniors and wants to see them have good enough outcomes so that they are pretty happy and definitely aren’t complaining to the school. Steering us to a successful ED outcome at a school down a tier from the HYPS would definitely accomplish this. There is no way we would be complaining if my son ended up at top 15 school. Also, every student who he helps gets in during the ED round is (a) a case off of his plate for the rest of the year and (b) someone who is no longer competing with the rest of his students in the RD round. His office works very hard to get as many kids as possible in during the ED round and I suspect he gave many kids the same advice he gave my son. For kids like my son, I think he was more concerned about them becoming cautionary tales than getting into their dream school, mostly because they have other kids that they are pretty sure are going to get into the HYPS in the early round. I don’t know how much these factors influenced our dean’s advice to my son, but I also want to point out that these are all very reasonable things for him to consider, if he did. They just weren’t perfectly aligned with my son’s individual goals.

Now let’s move to our coach. His company’s brand is entirely tied to how many kids they can get into the HYPS and other Ivies. Even if my son didn’t have a great shot of getting into the HYPS REA, if the company tells 100 kids to apply REA to the HYPS, maybe three get in and that adds to the prestige of the company (‘We have gotten 863 kids into the HYPS!’). I can even imagine there are financial incentives for the strategists who get their kids to REA to the HYPS and bonuses if they manage to get in. I have no specific knowledge of this, but I can imagine it.

Finally, let’s discuss the ‘independent’ coach. What motive could he have possibly had that would have biased his feedback? His life was utterly unaffected by what my son decided to do, right? Actually, maybe not. He was advising a bunch of other Los Angeles students at elite high schools including several at my son’s school. In other words, my son was potential competition to his students. If my son never applied to the HYPS then he could never take a slot from one of the kids that guy advises. Ultimately, this is the one person who I think might have intentionally gave my son bad advice, even though to me, at the time, he seemed the least likely to have any bias. Then again, I really don’t know how he viewed my son based on what I shared.

Ultimately, my son made the smart and practical decision to apply to a top 15, but non-HYPS, non-Ivy, school for the ED round. We had two people telling us that my son had no shot at his dream school in the REA round and that cautionary tale was looming large for us. I still think that it was probably the right decision not to REA to his dream school, but not for the reasons you might think. I’ll come back to this.

Lesson 16 – I too am an unreliable narrator. This one is quick. It should go without saying that in the same way you should take the advice of others with a grain of salt, you should take all of my advice the same way. My advice is shaped by my particular set of experiences and the lenses through which I took in those experiences. I think my experience is likely to be relevant to some subset of parents, but it may be less relevant to you and that is completely fine.

Lesson 17 – The ‘Why us?’ essay. After you have chosen the schools your child will apply to and what round to apply to each school in (ED, EA, RD, etc), the most important part of the application process is the essays. By this point your child’s scores and accomplishments are set in stone (though there is an art to presenting them the right way in the limited space you are given). What your child can control at this point is the story they tell about themselves through the essays they write. Expect to write one long essay for the common app which most schools will look at, a series of short essays for the UC application, and then most schools will have a few ‘supplementary’ essays that they ask students to write in addition to the common app essay. I firmly believe that the ‘why us?’ essay that each school asks for is among the most important. It is probably also the hardest essay to write well.

In the ‘why us?’ essay, a school will ask your child to spend 150-300 words telling them why they and that school are truly perfect for each other. Your child cannot say ‘Your school is awesome with excellent resources’. Rather they have to show that they really really know the school and really understand how the specific resources and opportunities at that school will allow them to move forward on the goals that they have already been working towards throughout high school. Your child also needs to look like someone who will bring something to that school’s community that they really want. Your child needs their essay to help them look like one-of-one while also coming across as completely authentic. This is an incredibly tall task for any 17-year-old high school student. It will be easier if you crafted a strong narrative that drove your childs ECs and coursework. It will also be easier if you are really choosing schools based on fit, because fit is essentially the answer to this essay. But if your child is aiming to get into a top school, they are probably applying to at least half of the top 15 schools and some will not be a distinctly good fit for your child.

My son initially had two types of ‘why us?’ essays. For most schools, my son talked about specific classes and clubs at that school that were up his alley given his entrepreneurship/business narrative and sometimes he mentioned a new club he would like to create at that school. However, for a handful of schools that we had visited, my son had had an amazing experience and had fallen in love with the school through the tour or other people we met on campus. These ‘why us?’ essays felt really different because the school had really become one-of-one for him. At his dream school, he saw a flyer looking for other students to join them in founding a company and it had little tear off strips at the bottom with contact info. my son compared this to other schools where you might see flyers with a band looking for a drummer, but given that my son wants to be an entrepreneur, this is the kind of band he wanted to join. He wrote about being excited to post his own flyer, looking for other students to join him in building a start-up. It was personal and real and created a specific image of an experience he had that linked him to the school and connected to my son’s singular narrative going back years.

About a week before his RD essays were due, our son realized he was about to submit about a dozen applications with ‘why us?’ essays that were pretty generic. Although well written, they could have come from 1000 other applicants. There was a huge chasm between these essays and the two he wrote for the schools that he had fallen in love with on the tours. He decided that he needed to rework all of these essays if he wanted to stand out. He dug deep to find a more personal connection with most of these schools and ultimately submitted much stronger essays.

I teach writing to undergraduates and I tell them that that one of the hardest but most important things to do to become better writers is to throw away what they have already written. The first time you write an essay, you are mostly writing it for yourself, to figure out roughly what you want to say. Often, the thesis sentence doesn’t appear until the very end because that is when the student figures out what their thesis is. If you write an essay and then put it away for while you might get enough distance to see that the current essay isn’t quite what you need. But we treat our existing words as too precious to toss and so we tend to try to rework our writing, trying to improve the bad into something workable. Instead, think of what you have written so far as an initial sketch and now you are going to paint the masterpiece. You don’t need the initial sketch anymore. That was something you did just to get your brain ready to write the version that matters. Throw away the generic version, dig deep, and try again. Eventually you will get to something much better and for the application essays this is really worth doing.

Lesson 18 – TikTok is your friend. There is a lot of nonsense on TikTok but there are also amazing resources there for learning about the college application process and getting up to the minute information. I probably follow a dozen college coaches on TikTok, but there are two that I think really stand out with their timely and useful perspectives. I highly recommend following Andreas (@ivy_roadmap) and Brandon (@tinecollegeprep). They put a ton of free content out because it’s a way to advertise what you will get if you choose to hire them. If I had it to do over, I might have tried to work with one of them over the company we did work with. They have very different personalities, but they really helped steer us in the right direction through the content they shared. When results started coming out, Brandon was particularly good at giving updates about how the admissions process went at each school. Andreas has some real out of the box thinking and I first found him when I was looking to see if anyone else thought ED was a scam like I did. He has a ton to say about this. He is also way more snarky (which I enjoy). I can’t imagine going through this process without following them online. Of all the things that I did to try to reduce feelings of uncertainty, following them probably was the most effective.

Lesson 19 – The cautionary tale is not what you think. Here is 2025’s cautionary tale. Zach Yadegari had a 4.0 unweighted GPA, a 34 ACT, and started a company, Cal AI, that generated $30 million in revenue in its first year. This kid is super impressive and has a very bright future. Despite this, he was rejected almost everywhere he applied including all of the HYPS, HYPS-adjacent schools, and the Ivies. This is the kind of story that comes out every year that makes you think ‘OMG, we could end up with our amazing child not getting into any good schools. Maybe we should lower our expectations and apply to more mid-tier/top 50 schools and not apply to the very top schools. If Zach couldn’t get in, what chance does my kid have?’

Two years before that, Stanley Zhong was similarly rejected by nearly all of the top schools despite having a 4.42 weighted GPA, 1590 SAT, and founding a successful startup. His consolation prize was that he was offered a full-time job at Google! Another really impressive kid.

We will never know exactly why each school rejected these students, but the consistency of the rejections from so many universities suggests that there were likely red flags that we don’t know about when we hear these little snippets about their record. The Yadegari case is unusual in that he actually posted his common app essay. You can read it here: https://medium.com/write-a-catalyst/zach-yadegari-30-million-net-worth-and-a-college-rejection-fc05ee28f771

A lot of folks have commented online that you can’t start an essay to get into an elite college by saying “I will never go to college” like Yadegari did. Maybe that is what got him rejected, but that seems too simplistic given that the overall theme of the essay is about his transition to wanting to go to college and I think in some ways this is a very strong essay. More likely, the problem was that he concluded “I’m going to college” but he never said why or how he thought college would add to his ability to get where he wants to go in life. If I had to guess, this is why he didn’t get into an elite school. He didn’t give schools a real reason to believe he needed them. There is one other red flag. He shared online that he has a 4.0 unweighted GPA, which at first blush sounds fantastic – straight A’s. The fact that there is no weighted GPA listed leads me to believe this student may have few, if any, honors and AP classes suggesting his weighted GPA is also close to 4.0 which is far less impressive. The broader point here is that the cautionary tales always feel impossible – how could someone with such an impressive record not get in to top schools? But if 16 of 18 schools reject the student, I can guarantee that if you got to see the entire application (not just what they choose to reveal online), you would probably reach the same conclusion that the AOs did.

So the real lesson is, worry little less about the cautionary tales. They are never what they seem to be on the internet.

Lesson 20 – Strap in! Getting back your results is an emotional rollercoaster of uncertainty and overinterpretation. If your child is applying in the early round, you will start your emotional rollercoaster ride in early November and then hit your first big drop (which can be thrilling or terrifying) in mid-December when your ED and a few EA results come back. I’m going to share our rollercoaster ride to give you a sense of the waves of uncertainty that hit us over the course of the process. I debated whether to include this because I am revealing my son’s results (with his permission), but I know that if I was reading this, I would want to see this part.

My son applied ED to Northwestern, a top 15, non-HYPS, non-Ivy school. He was very happy with this decision and felt like he had about a 50-50 chance of getting in there. He said he would have no regrets if he got in and his process was over. He also applied to two elite EA schools (MIT and University of Chicago). Beyond those, he applied to three top 30 schools, and five other targets and safety schools during the EA round.

At the end of November, he applied to 7 of the 10 UC campuses in a single application. He did not have particularly high hopes for the UCs because they do not look at SAT scores and that was one of the strength’s of his application.

In mid-December, he found out in quick succession that he was deferred from Northwestern, MIT, and University of Chicago. Deferrals mean that your child’s application will be moved to the RD round and considered there, but each of these deferrals meant something different. MIT pretty much defers everyone it doesn’t accept in the EA round so it doesn’t tell you much. University of Chicago pretty much does the same and at least for kids from my son’s high school, it is really clear that if you don’t apply either ED or ED II, you are unlikely to get in. University of Chicago seems to be a school where if you commit to them and only them, and have very strong scores, there is a decent chance things will work out.

But the Northwestern deferral gave us mixed emotions. On the one hand, we had heard they only defer about 2% of students so this must mean that they read my son’s application very positively and this might be a good sign that other top schools would read his application positively. Given his non-traditional ECs, we knew different AOs might read his application very differently from one another, so we thought this was a good sign that an amazing school must have viewed his application favorably. On the other hand, we also felt ‘So close! Why couldn’t they have just accepted him? Now he has been thrown back into the RD pool with everyone else. Being a cautionary tale is still on the table. Uggh!’. On the other, other hand, maybe it’s a good thing because now he gets to have results from all 30 schools and we want to see all of those results. On the other, other, other hand, we had heard that Northwestern deferrals have about a 15% probability of getting in during the RD round which is 3x the probability for everyone else, so maybe this will still be our school. And getting in after so many other rejections in between, my son will appreciate it so much more than if he got in ED. Yes, we had each of these four thoughts many times over the next month. It was a lot.

One thing no one tells you is that even though many schools have EA deadlines of November 1, many do not tell you the outcome until well after you submit your RD applications in January. We naively thought my son would hear back from all of the EA schools before he submitted his RD applications. In fact, even though my son applied to 10 EA schools (and 1 ED school), he did not hear from 8 of the EA schools until mid-January after his RD applications were submitted.

Next up, my son had to decide if he should apply to University of Chicago for ED II. This application was due at the same time as RD applications but if you get in you have to withdraw all other applications and commit to your ED II school. My son was really torn about University of Chicago. He had almost applied there as his ED in the first round. He loved the campus when he visited and was super impressed with their academics. He was also interested in pursuing finance and University of Chicago is definitely a ‘target’ school for investment banking firms. These firms actively recruit from about 10 places and University of Chicago is one of them. Finally, for the rest of your life, no one will ever doubt your intelligence if you graduate from University of Chicago. But my son just couldn’t shake the feeling that it was not a good fit for him socially. He is hyper social and University of Chicago’s own dean once referred to University of Chicago as ‘where fun goes to die’. To be clear, my son was still really excited about the prospect of going there, but he was on the fence about whether he wanted to give up his ability to consider 29 other schools if he did get in there. In the end, he allowed his University of Chicago deferral from the EA round to become an RD application rather than an ED II application. He knew this was probably the kiss of death for University of Chicago because from his high school, they almost never take students in the RD round.

In terms of submissions, he finished things off by applying to 12 RD schools in early January, including his two dream HYPS (Stanford and Harvard) and three other Ivies (Dartmouth, Columbia, and Wharton at University of Pennsylvania). By mid-January he started getting back all of the other EA results from his November 1 submissions. Here were his final EA results. He had 4 deferrals (I already described most of these). He got accepted to all three safeties that he applied to in the EA round. These came first and did not excite my son – getting into a safety school is never exciting. Then my son got into his first top 30 school (UNC) and felt pretty good. A week later, he got into his first top 25 school (UVA) and this was the first school he was genuinely excited about. He knew it was my dream school that I had gotten rejected from a million years ago. UVA is also a strong school for investment bank recruitment.

Back to waiting. We were feeling pretty decent about my son’s position. He had gotten into two really good schools (no gap year for my son!) and had almost gotten into a top 15 in the ED round. Hopefully this was a sign of more good things to come.

The first chunk of decisions from the RD round were a blur. He got into two safeties. But then got waitlisted at three UCs and rejected from a fourth UC. At this point, I was really starting to worry again about the fact that we passed on the opportunity to ED II to University of Chicago. We seemed to be getting not so positive signals. In the next batch of results, all but one of the deferrals became rejections (including Northwestern) and my son got two more waitlists from top 30 schools.

Up to this point, nothing shocking had happened in either direction. Positive and negative things had both happened, but nothing shocking. Then my son got a phone call from the Dean of Admissions at Washington University (just about a top 20 school). my son was offered a full ride to go to their business school. This was a massive ‘holy shit’ moment for my son. Wash U is a truly outstanding school that my son would be so lucky to attend and they were offering to pay for it. My son was on cloud nine, but the feelings became more complex over time. This school was not the best fit for my son. Wash U’s business school is really great for consulting but not so great for finance, where my son thought he might be headed (my son’s interest in finance grew during the application process). But this was also a lot of money. While I loved the idea of not having to spend all of that money, I have been saving for my son’s college for 18 years so that my son wouldn’t have to consider money as a factor when choosing a school. He felt really bad, but when he thought about it, he probably still preferred UVA which would have cost way more, because it was a better fit. Finally, we took the scholarship from Wash U as a renewed sign that there could be more good news on the horizon. This school only gives out 10 of these scholarships so they must think my son is going to get into one of the top top schools and are trying to woo him away, right? Of course, the AO at this school is only one reader and could be mistakenly assuming other readers would read my son’s application as positively as he or she did. So much uncertainty!

Things really settled down with my son’s next outcome. He got into Georgetown, a top 25 school, but more importantly, he was accepted into their business school which is a top 5 business school in the country for getting into investment banking. This was a school that I grew up thinking of as just outside the Ivy league and it had everything my son wanted. This was the first time where we all really started to imagine my son at a particular school (as hard as giving up that full ride would be!). It was also the first time I thought, “This is probably a better outcome for my son than his ED school, Northwestern, since this place is better for finance and might have a stronger global brand”.

For me personally, a real gut punch came next. My son got flat out rejected from UCLA. My wife and I have been professors at UCLA for a combined 45 years and my son clearly had good enough scores to be a student here. They could have at least put him on the waitlist. That one really hurt – though to be clear, it hurt me, not my son. We live two blocks from UCLA. My son went to pre-school and middle school there. He has gone to summer camp there. He did research on campus. He has had more than enough of UCLA and would not have chosen UCLA over his other options. But for me, it hurt.

The next big day was Ivy Day. This is the day when all of the Ivies release their RD results. My son had applied to four Ivies (Harvard, Dartmouth, Columbia, and Wharton at University of Pennsylvania). Of the four, we only had a good feeling about Dartmouth. I think since I got my PhD at Harvard, we held out some magical hope that Harvard might come through for my son even though he was not a legacy. In reality, my son didn’t get into any of the Ivies. He got waitlisted from Wharton and rejected from the other three.

I’ve seen so many kids on TikTok opening their Ivy Day decisions and screaming in triumph, but for my son the Ivies had been a total a bust. Though one more school decided to mooch in on the Ivy Day action and because of this, my son found out he had been accepted to the Haas School of Business at Berkeley which is tied for the #2 undergraduate business school in the country. We were all thrilled. My son still wanted to visit Georgetown because he liked the idea of a smaller school, but he was strongly leaning towards Haas. He told all of his friends. We started thinking about buying him gear. I started thinking about the money I would save from him going to Haas as a California resident.

Yet the very next day, my son found out he wouldn’t be going to Haas after all. That’s because he found out he had been accepted to Stanford, his absolute dream school from the beginning. This is the school where he had seen the flyer from someone looking to join their start-up. This is also the school that the ‘independent’ coach had said my son should not bother applying to at all. My son sobbed uncontrollably for five straight minutes. He had worked so hard for four years to get to this point. I don’t think he deserved it more than thousands of other kids who were rejected, but I do think he deserved it as much as anyone else. Incidentally, we all agree with our dean that my son should not have applied to Stanford REA, but not for the conventional reason. Rather, my son’s writing got so much stronger and his essays became more compelling. If he had applied to his dream school in the REA round, I suspect his essays would have been weaker and he would have been rejected.

Stanford is only one of two schools with no undergraduate business school that accepted my son. The other was a safety. But Stanford as a campus is the ultimate business environment for a student. It is the most entrepreneurial campus in the country with its students going on to found companies like Google, Yahoo, Instagram, and Snapchat. For my son’s goals, there is no place with a better fit for him.

What are the big lessons here? Going forward the process is so incredibly uncertain, but if your child sends a clear signal about who they are they might get a clear signal back from schools. My son got rejected by virtually every college that did not have an undergraduate business school or a profound entrepreneurial culture. A ton of top schools couldn’t care less about my son’s great scores because he did not look like a liberal arts student to them. To be fair, they weren’t wrong. They got it right. He isn’t a liberal arts kid. On the flip side, the colleges that did have an undergraduate business school or a strong entrepreneurial culture overwhelmingly accepted him.

So, develop a plan as early as possible about how your child wants to present themselves authentically and then stick to that plan in deciding what classes to take, what ECs to do, and what summer activities to engage in. Do a passion project that aligns with this plan. Apply broadly and then hope that schools see your child the way they tried to present themselves and they will likely get in somewhere that is a good fit for them.

Here is not a takeaway – my son was destined to get into his dream school. It’s easy to see it that way because he got in. But, we did not think that would happen. We felt bad that we had toured Stanford before other schools because we thought it would make it harder for him to appreciate wherever he ended up going because Stanford is so beautiful. In the end, my son was absurdly lucky. I truly believe that if a different Stanford AO had read his materials he could have easily been rejected. That said, my son would have been incredibly lucky to get attend to any of the last three schools he was admitted to (Haas, Georgetown, Wash U). Luck truly plays a part because each AO will see your child differently.